A European Journey #65 – Kensington (England)

The Reformation of the sixteenth century in Northern Europe had several significant outcomes. Most crucially it was a return to the truth of salvation by grace alone. But the Reformation also promoted the use of native languages and even led to the independence of the judiciary.

For the last stage of this miniseries in which we have explored the events that triggered the English Reformation, we will visit London once again. Last time we were at Trinity Square Gardens, near Tower Bridge. But today we will visit the royal borough of Kensington and Chelsea, which is located in the Western part of the city. There we find the Victoria and Albert Museum, half a mile South from the famous Hyde Park. With a collection of over two million objects, this is the world’s largest museum of arts and design.

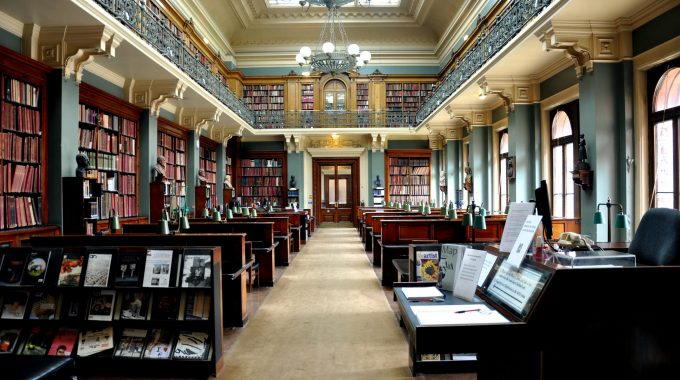

One of the main sections of the museum is the National Art Library. It contains 750 000 books, paintings, drawings, prints and photographs. There are writings from many prominent people, such as Leonardo da Vinci, the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza, Giovanni Boccaccio, Dante Alighieri, François Rabelais, Molière, Charles Dickens or Beatrix Potter, to name but a few.

In this library we can also find an early version of a Church book from 1543, which is titled A Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for any Christen man, set furthe by the kynges majestie of Englande &c. This was obviously a very long title and this is why it is more commonly known as the King’s Book. The reason it is named after the king is that it was commissioned by king Henry VIII. Nevertheless, the main author of the book was the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer.

The King’s Book is one of the clearest testimonies of the internal struggles that the Church of England faced following its separation from Rome.

But before I talk about the book, let’s return briefly to what happened in those days in England. During our last four episodes, we discovered that it was the marital instability of king Henry VIII that led to the beginning of the English Reformation in 1533. Then the Church of England became divided in two opposing groups, the Reformed and the Roman Catholic sides. During the first years after the separation from Rome, the Reformation seemed to gain the upper hand. But soon, the Roman Catholic opposition began to grow and influence the king.

The turning point of the struggle was the execution of Thomas Cromwell in 1540. This lawyer had been one of the most powerful men of the English court and had favoured the Reformation. After his death, even though the Reformer Thomas Cranmer was still Archbishop of Canterbury, the Reformation stagnated.

The doctrine of the Church of England reflected these unsettled times. Several statements of faith had been drafted and then replaced by others, before the Thirty-Nine Articles, also called the Bishop’s Book, were published in 1537. These were short articles defining the main doctrinal lines of the Church of England. Six years later, the King’s Book was published. The book was a fuller explanation of the doctrine presented in the Bishop’s book.

Let’s take a brief look at the contents of the book.

Some of the affirmations tended towards the theology developed by Martin Luther. For example, free will is defined as follows: (Free will is a) certain power of the will joined with reason, whereby a reasonable creature without constraint in things of reason, discerns and wills good and evil ; but it wills not that that is acceptable to God unless it be helped with grace, but that which is ill it wills of itself. So man had free will but it was too corrupted to be able to choose God’s will. Man needed God’s grace. Other points, however, still reflected the doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church, such as invoking the saints or praying for the dead. Also the idea that good works were necessary to obtain salvation remained.

In addition to doctrine, the King’s book had a direct influence on the structure of society. For example, it contains points that can be seen as early steps toward the independence of the judiciary. It was no longer possible for the clergy to sentence heretics as had been the case in the Roman Catholic context. Now the clergy was placed under the authority of the civil magistrates. Obviously, this was a practical expression of the supreme authority of the king over the Church. Nevertheless, the idea that the clergy should be under the authority of the civil magistrate was new.

Also we discover that the use of the native language is explicitly promoted in the King’s book. A particular instance of this is found in the preface where there is an exhortation to private prayer in the native language. By understanding what we ask God, we are able to pray more earnestly and desire more fervently what we ask for.

The sixteenth century was both a time of exciting changes and of painful struggles in the British Isles. However, nearly five hundred years later, this book in the Victoria and Albert Museum stands as a shining testimony to the progress that the Reformation brought in England.

See you next week somewhere else in Europe.

Cédric Placentino

Schuman Centre convener for Italian and French Europe

Follow A European Journey here.

Picture: Public Domain (source: Wikipedia)

This Post Has 0 Comments