Year Zero

This coming week European countries will commemorate the end of World War Two in different ways.

The Netherlands, for example, will hold solemn ceremonies across the nation on Tuesday, May 4, to remember those who lost their lives. In Amsterdam, the king and queen – without the usual public crowd – will lay wreaths on the Dam memorial opposite the palace. The next day the Dutch celebrate the liberation brought by Canadian, American, Polish and British troops, with restrained exuberance under Covid restrictions.

Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians have little to celebrate on May 8 when in 1945 one occupier was simply replaced by another. They brace themselves for the noisy celebrations the next day when ethnic Russian residents drive through the streets hooting horns and waving Russian flags.

Images of victorious soldiers giving out chocolates, cigarettes and kisses remain in our imaginations (at least in western Europe) as depicting the end of fighting and beginning of blissful peace. The reality, however, was very different.

The euphoria soon gave way to the awful aftermath of violence and rape, betrayal and unfaithfulness, rejection and deceit. Bitterness and vengeance still ruled in many hearts. As one soldier wrote towards the end of 1945, ‘The bloody battles are over, but life’s real battle has only just begun.’

The old world had been destroyed. A new one was yet to be rebuilt. This was year zero.

Bronzen gods

Ian Buruma has written a history of 1945 with that title: Year Zero. Drawing from hundreds of eye-witness accounts and personal stories, he reveals the horrific conditions under which millions of disorientated Europeans, east and west, continued to live in despair, fear, hunger and deprivation.

His sobering descriptions help put our current deprivations in perspective.

Not only were the moffenhoeren, women accused of ‘horizontal collaboration’ with the Nazis, stripped naked, hair shorn, tarred, feathered and paraded through the streets; fraternisers with Allied liberators – who appeared to them like bronzen gods in their fresh uniforms – received similar treatment from Dutch youths, who felt rejected and humiliated after years in hiding or of forced labour in German factories.

A popular song after the war ran:

Many a ‘Dutch girl’ soon threw away her honour / For a packet of cigarettes and chocolate bar…

No Dutch boy will look at you again / since you left him in the cold…

Much of Europe remained occupied by millions of single soldiers for years to come – in the east, for over four decades. Veneral disease rates soared in the postwar chaos where medical facilities were scarce and bad hygienic conditions were rife. In Berlin, Ruinenmäuschen, ‘mice in the ruins’, girls and women lived in the shadows of the rubble selling themselves to soldiers for cash, food and cigarettes.

Hunger haunted the Dutch during the war’s last winter. The Zuiderkerk, close to where I sit to write, became a mausoleum with stacks of bodies unable to be buried in the frozen ground. Across the continent and even in victorious Britain, hunger and cold stalked the population. Long after V-E Day, many Brits still slept in London’s underground stations lacking food and heat. One visitor described Milan as ‘a slice of Hell; bloodless, undernourished people, dressed in any old cloth that could protect their skins.’ Another described residents of Budapest as ‘skeletally thin as the sketches of the human structure found in anatomy books, without any flesh and fat.’

Embarrassment

Revenge was a human but destructive reality of these post-war months. Red Army soldiers entering Germany read road signs in Russian saying: ‘Soldier, you are in Germany; take revenge on the Hitlerites.’ Marshal Zhukov’s orders read: ‘Woe to the land of the murderers. We will get our terrible revenge for everything.’ Soviet troops were given licence to rape German women in front of emasculated ex-warriors of the ‘master race’, as Buruma puts it, repaying humiliation with humiliation.

Massive expulsions and population upheavals following the Big Three decisions in Yalta of February 1945 visited further misery on millions: Germans moving out of Silesia in Poland or Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia; Poles, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians and many more ethnic groups. Surviving Jews returning home found themselves to be an unexpected embarrasment, especially for those who had taken over their homes and possessions. Likewise, returning POW’s and those forced to do heavy labour in Germany faced rejection and shame.

Add to all this the fear of Stalin’s growing aggression and it becomes clear that post-war Europe was suffering a severe case of post-trauma stress disorder. On what basis could a new Europe be built? How could democracy and rule of law be restored?

American support through initiatives such as the Marshall Plan, the UN and NATO were vital – but not sufficient. Forgiveness and reconciliation among Europeans, especially between Germans and French, was essential.

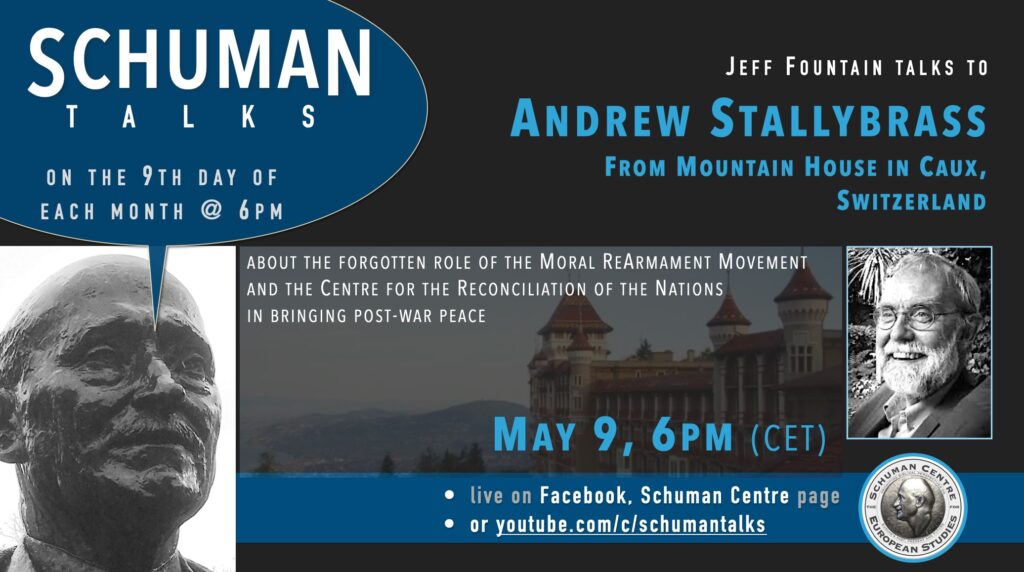

That’s a story for next week.

P.S. Don’t miss:

From the Look Up Centre, Romkje talks about lessons learnt from working with Corrie ten Boom; https://www.eventbrite.nl/e/corrie-ten-boom-and-me-tickets-152090836787 or YouTube: https://youtu.be/Y4A65zTS8oQ

This Post Has 0 Comments