Building a Common European Memory

Memory is one of the key factors to our national identities. We remember similar events and persons and these bind us together.

Artists are key persons in visualising our national memory and sometimes they are also critical to our national history. Another way of being critical to our national memory is to place our history in the wider perspective. Usually we commemorate a glorious event. We have our national heroes who liberated our country. We sing songs in honour to them, we have artists producing all kinds of artworks to glorify the heroes and the event. But there is always another side to it because the glory of our nation is usually the suffering of another one. Very often our glorious past has made victims but we don’t commemorate that. We just look at our side and that is our national story.

I have been brought up in the Netherlands and I have learned to hate the Spaniards because we fought for eighty years and we managed to kick them out. So we still have songs and customs in memory of that. The Spaniards are our enemies and this can be felt whenever there a Dutch football club plays against a Spanish club. When our favourite national football player, Johan Cruyff emigrated to become the coach of Barcelona, he was accused to be a traitor. People felt that he had betrayed our nation.

What is happening in Europe is that all these nations which have their own memory are being put in one lot. They are now a community of nations, and this is a way to help us to see our national history in the wider European perspective. We have done a lot of good to our neighbours but also a lot of harm. Usually we don’t think about this aspect. We think that that is other people’s business. With regards to our Dutch history with Spain, Spanish people have a totally different version of history, one that is very humiliating for the Dutch. That is their pride.

But how do we get beyond that and commemorate these events against those who collaborated and with those who were victims of that? How can we make it a common memory so that we can construct a collective European memory that binds us together, something that we remember together, for example not something to be remembered by Romanians only, but something that Hungarians and Romanians can commemorate together? This would be a good thing and it would create a collective common memory. That is how peoples and identities are fed and nourished. There are some examples of that. In many places in Europe, there are memorials for the holocaust. There we find people of all nationalities commemorating it because they realize that it was not just the Nazis, but also the collaborators. Every nation has taken part in this horror. So nobody can blame someone else because we all have something to blame ourselves. This is precisely what brings us together in a common humility, when we say ‘This was a disaster. We have to commemorate it and we were all part of the problem.’

Willy Brandt was the first German Chancellor to visit Poland after World War II, in 1970. The official program was very tight. At some point, Willy Brandt, who was raised from a Protestant background, left the protocol, stepped out of the program, and ran out of the crowd, to the front of the memorial, where he knelt down for two minutes in total silence. This was his way of saying sorry and of paying tribute to the Polish people. This simple act has had such a tremendous impact on the Polish people. So for the first time, before the war memorial in Warsaw, a German and a Polish political leader were standing together and commemorating the holocaust. Brandt associated himself to the memory of the Polish people. That was the way to bring these people together and it paved the way to what was called ‘Ostpolitik’.

This is such a telling example of how we, in Europe, can also commemorate together, instead of making it a nationalistic pride event in which the bad guys are always on the other side of the border, while we are the good guys. This is so dividing.

Another example of such a commemoration happened in Verdun (France). Verdun was a complete butchery during World War I. There, for four years, the French, the English and the Americans fought the Germans in a trench warfare, where more than a million soldiers died. Even today, remnants of bodies are still found in the fields. There is in Verdun an enormous memorial and commemorations are always done by the French. In 1984, the French President François Mitterrand had the tremendous idea to invite German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to come to Verdun. In the wake of the German-French reconciliation that started with the French Foreign Affairs minister Robert Schuman and the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer after the second World War, Mitterrand had to make one step forward. Verdun was a place of humiliation for Germany because that is where they lost the First World War. So there was obviously a lot of tension because all the nationalistic feelings, this humiliation, came out. Then Mitterrand and Kohl did something that was not prepared. Kohl reached out his hand to Mitterrand who could not refuse it. Mitterrand took Kohl’s hand in front of the memorial where his people had been defeated. This handshake has given us one of the most iconic pictures.

This is how we should commemorate our national events. We should invite our enemies to commemorate together with us. This is what will be done in Normandy in June 2019. 2018 was already a preparation. For the first time, representatives of the Bundeswehr (German Army) were invited to take part in the commemoration of the landing of the allied forces in Normandy that started the end of World War II, in 1944. It is usually a very upbeat event where all the Western leaders tell each other how good they are and how well the world is after their intervention. However, there was never a German, an Austrian or a Russian there. In 2018, some troops of the Bundeswehr were invited. Even though they were low profile, they were part of the commemoration. In 2019, Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin will be there so that they can stand there together. That can be a moment of going beyond our national history and creating a collective memory so that people can appropriate this event on both sides of the line. The Germans can also say: ‘Thank God, we got rid of the Nazis. Thank God that there were Americans and British people who risked their lives. It was also for us that they did it and we can be grateful together.’

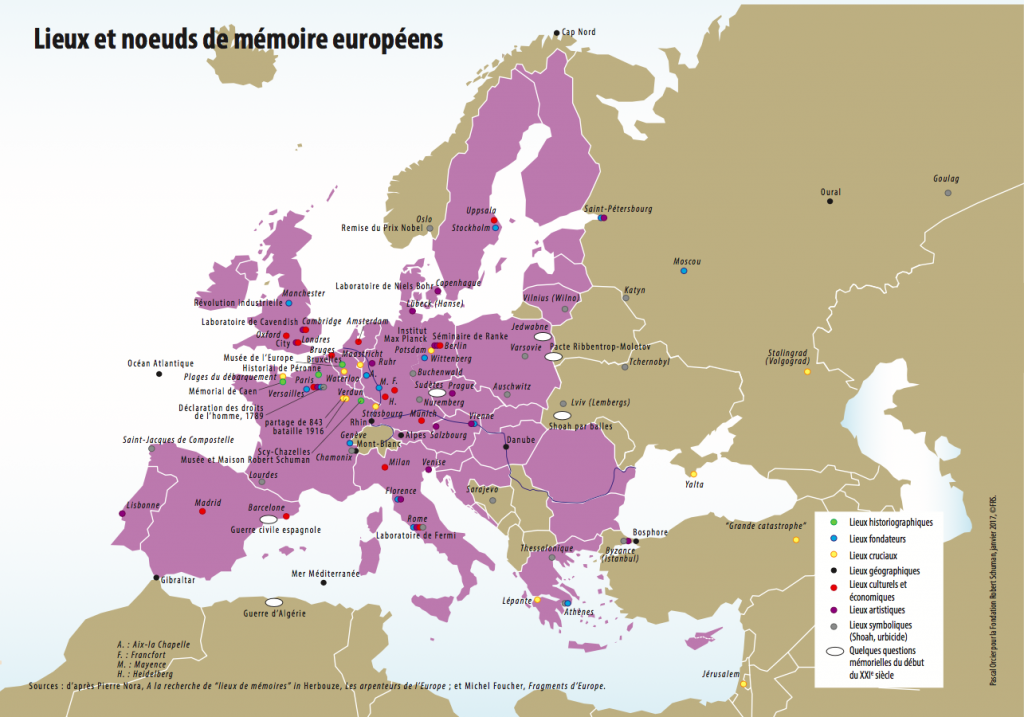

There are so many other places in Europe where there is a national memory but where there is also another side. For example, the Holodomor memorial in Kiev, which commemorates the great starvation during the Stalin Era, could become a place where Russians and Ukrainians stand together. Or how about the Hill of the Crosses in Lithuania? Here is a map that from the Robert Schuman Foundation which locates spots in Europe that have a common memory and that could be used to commemorate things together with other people. They are spread all over Europe.

Let us be European in the way that we commemorate our national memory.

Dr Evert van de Poll

Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven and a pastor with the French Baptist Federation.

This Post Has 0 Comments