The divides of Europe

The message of the Gospel was the primary life source of the European continent. Yet, the history of the Church, with its internal divides and its struggles with foreign religions, also influenced the shaping of Europe. In this article, Evert van de Poll explores some aspects of it, in particular the relationship between Christendom and Islam.

This is an excerpt of Evert Van de Poll’s book ‘Christian faith and the making of Europe’. To be published soon.

Christianity is a major, if not the main common denominator in the history of Europe. At the same time, it has also shaped its cultural diversity, more than anything else.

Different interactions with Christianity

All the peoples of Europe have been marked by an interaction between their culture and Christianity, but this has taken different forms. For a start, when the peoples within the Roman Empire were Christianised, they were to a large extent Romanised, and their languages Latinised. But when the tribes that lived further north were Christianised, their cultures were not suppressed but rather transformed through the influence of the Church. They kept their languages, although they adopted much of the ecclesiastical language which was also the common language for the learned, Latin in the West and Greek in the East.

Moreover, the Church had a dominant position, but she did not exert her influence in the same way everywhere. In some cases, prelates acted in alliance with the existing political powers, in other cases they supported opponents and rivals to the rulers in power.

Finally, as divisions within the Church developed into military conflicts, they shaped the political map of Europe. The prime example is the rift between Protestants and their opponents within the Roman Church, which gave rise to the religious wars during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Each country had its particular Christian tradition. In each country there was the alliance between the rulers and a particular church. As a result, Christianity took on different national colours. In some European countries, the dominant Church, clearly nourished nationalistic sentiments. One thinks of Orthodoxy in Russia, Lutheranism in Germany, and Roman Catholicism in Spain.

Dichotomies and Europe’s borders

Despite their diversity of ethnic origins, languages, cultures and despite their different experiences with the same Christian religion, the peoples of Europe are interconnected by regional affinities. A closer look at the diversity reveals a certain pattern. Europe consists of socio-cultural regions shaped by historical religious dividing lines. When we try and map these regions, we can draw some kind of a cross over the continent.

This approach is not new. Faced with the question where to draw the limits of the geographical and cultural space called Europe, authors often revert to major political and religious schisms in history, that have sealed it off from other regions.

Polish author Oskar Halecki is often quoted when he speaks of the two dichotomies that have determined the origins of Europe, as well as its development. To begin with, the division between Occident and Orient, were introduced by the ancient Greeks and followed by the Romans. They distinguished the regions around the Mediterranean (West) covered by the Roman Empire, from the regions to the east. When the Muslims conquered the Middle-East and North Africa in the 8th century, a second dichotomy arose. The Mediterranean Sea that had united the Roman world, now became the southern border of the Christian world called Europe, separating it from the Islamic world in the south and the Middle-East.[1]

French author Rémi Brague follows the same approach and summarises:

Europe as it can be pointed out today on a world-map, can be considered as the result, the residue of a series of dichotomies, that have emerged along two axes, one dividing eastern from western regions, the other dividing northern from southern regions. They go back to several millennia.[2]

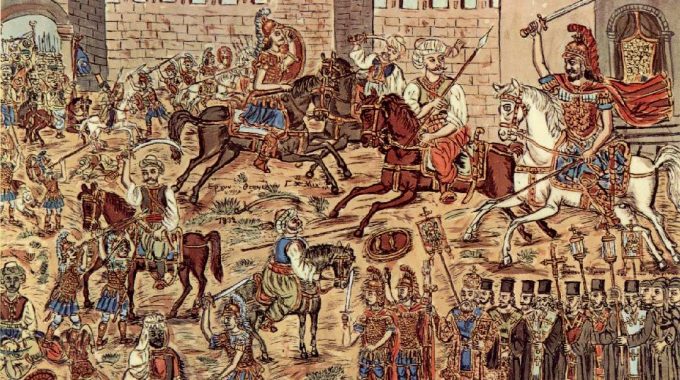

In the mind of the peoples of Europe, the Christian-Muslim divide has remained the southern border of their realm, even when Muslims succeeded in crossing the border. First they maintained a presence in the Iberian Peninsula for many centuries, but they were gradually pushed back, until their last state, the kingdom of Granada, finally fell in 1492. Meanwhile, the Muslim Ottomans had conquered the remnants of the old Byzantine Empire, in 1453. They imposed their rule in the south-eastern Europe till the end of the nineteenth century. During that time, the majority of the population remained Orthodox or Catholic, while the military, the civil servants and some people groups converted to Islam. Their descendants are found in Bosnia, Albania, Kosovo, parts of North Macedonia and Bulgaria, and in the European part of Turkey. Let us not forget that Istanbul, ancient Constantinople, is a metropolis of a Muslim country on European soil!

Dr Evert van de Poll

Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven and a pastor with the French Baptist Federation.

Image: The fall of Constantinople by Theofilos Hatzimihail (public domain, source: Wikipedia)

[1]Oskar Halecki, The Limits and Divisions of European History.

[2]Remi Brague, La voie romaine, p. 16.

This Post Has 0 Comments