Demography is destiny (Part II)

For the first part of the article, click here.

Interest in the link between religion and fertility has increased remarkably in the last twenty years.

An online Religion and Fertility Bibliography now runs to more than 700 books and articles. The societal consequences that sustained low fertility levels are having across a whole range of issues is explored at length in Poston (ed., 2018) Low Fertility Regimes and Demographic and Societal Change. The final chapter in Poston’s book deals with Religion and Fertility.

In it, Ellison et al investigate the effects of fertility changes on religiosity making use of four responses from the World Values Survey data in a very similar way to our own Nova Index of Secularisation in Europe (NISE) as described in the October 2010 issue of Vista. Their four measures were attendance at religious services, religious salience (the importance of religion in a respondent’s life), religious belief (specifically whether they believe in God or not) and private religiosity (measured by frequency of prayer). Multi-level regression analysis was then conducted on two independent variables, namely individual fertility (as recorded in their WVS response to the number of children they had), and country level fertility using Total Fertility Rate.

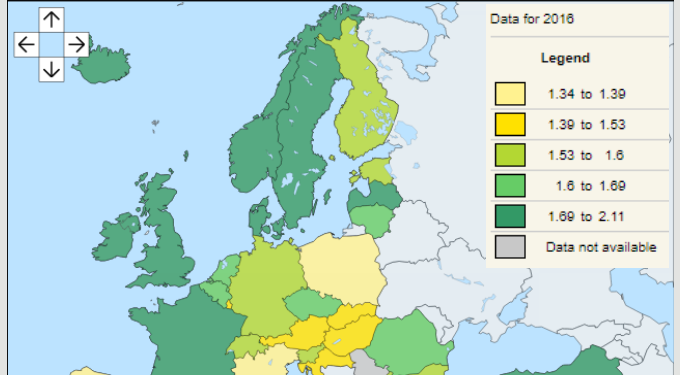

The results were clear: “both the individual level and country level fertility variables are significantly associated with all individual level religious variables in the anticipated directions” (p.223), that is to say, less religious people demonstrate lower fertility. Nothing surprising there. Where Ellison et al break new ground is in their reversal of the traditional causal relationship. Normally it is argued that as people become less religious, they have fewer children but these researchers suggest the inverse: declining fertility is what is leading to reductions in religious participation, salience and belief. In conclusion, they suggest “at least tentative evidence that the connections between religion and fertility may be bidirectional” (p.228).

Missiological Implications for Europe

These, and other, trends lead us to identify four key missiological implications for European mission:

1. The Greying of Mission. If half the European population will be over 65 by 2070 this will require a complete rethinking of mission priorities. Care for the elderly will become one of the principal activities of Christian mission.

2. The future of Islam in Europe. It is clear from recent migration and differential birth-rates that the number of Muslims in Europe will continue to rise. This poses a significant challenge for secular European societies but also for the church. Churches everywhere will need to help their congregations to engage in dialogue and outreach to their Muslim neighbours. They must also resist the rhetoric of populists and nationalists who would seek tolegitimise racism through “defending our Christian identity.”

3. Migration and the future of the European Church. Slow, gentle and silent demographic effects can have a profound impact over the long-term. The arrival of millions of Christian migrants from the rest of the world has been largely ignored yet these “new Europeans” are renewing and changing the face of Europe’s churches. Their passion, vibrant spirituality and confidence in the agency and power of God are no less of a challenge to secular Europe than Islam. If European churches and migrant churches can learn to work and witness together this can have a powerful testimony in tomorrow’s Europe.

4. “Go Forth and Multiply”. Rodney Stark (1996) has shown how the favourable fertility and mortality rates of the early Christians relative to the pagan population helped to fuel a 40% growth rate over several centuries. Could this happen again? If Ellison et al are right, then an increase in the religious population in Europe will require an increase in fertility rates among European Christians. Perhaps one of the most radical things that young Christians can do today is to get married and have a (large) family.

Secularisation is not the “telos” ofhistory. Predictions of the demise of Christianity in Europe don’t take into account the promise that Jesus made to Peter that “on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18).

The destiny of the church depends on more than demographics but we must not ignore the insights that demography provides to the future of Christian mission in Europe.

Jim Memory

Co-editor of Vista Magazine.

References

Ellison, et al in Poston (2018) Low Fertility Regimes and Demographic and Societal Change, Cham: Springer.

European Commission (2018) The 2018 Ageing Report, https://ec.europa.eu/info/ publications/economy-finance/2018- ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary- projections-eu-member-states-2016- 2070_en

European Environmental Agency (2016), https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and- maps/indicators/total-population-outlook -from-unstat-3/assessment-1

Kaufmann (2010) Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?, London: Profile.

Pew Research Center (2017) Europe’s Growing Muslim Population, www.pewforum.org/2017/11/29/europes -growing-muslim-population.

Pew Research Center (2018) Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues, www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/ eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on -importance-of-religion-views-of- minorities-and-key-social-issues.

Stark (1996) The Rise of Christianity, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

This Post Has 0 Comments